Beginning Programming Lesson 02

Now that you have your setup ready to go, we can start writing some code! Note that we are just touching the surface of the topics covered in this lesson, but the sooner you start writing code, the easier it will become to understand the topics better. Plus you are more likely to continue, if you feel like you are accomplishing something, rather than learning more and more theory.

You can download the file here. I suggest creating a folder to store all the files for this and future examples. Also create a sub-folder for each individual lesson, since they all will be named main.go. Open it up in VS Code, and open a terminal. Make sure you are in the correct folder/directory by using the pwd command. Use the cd command to change directories if needed. Then go ahead and run it by executing:

go run main.go

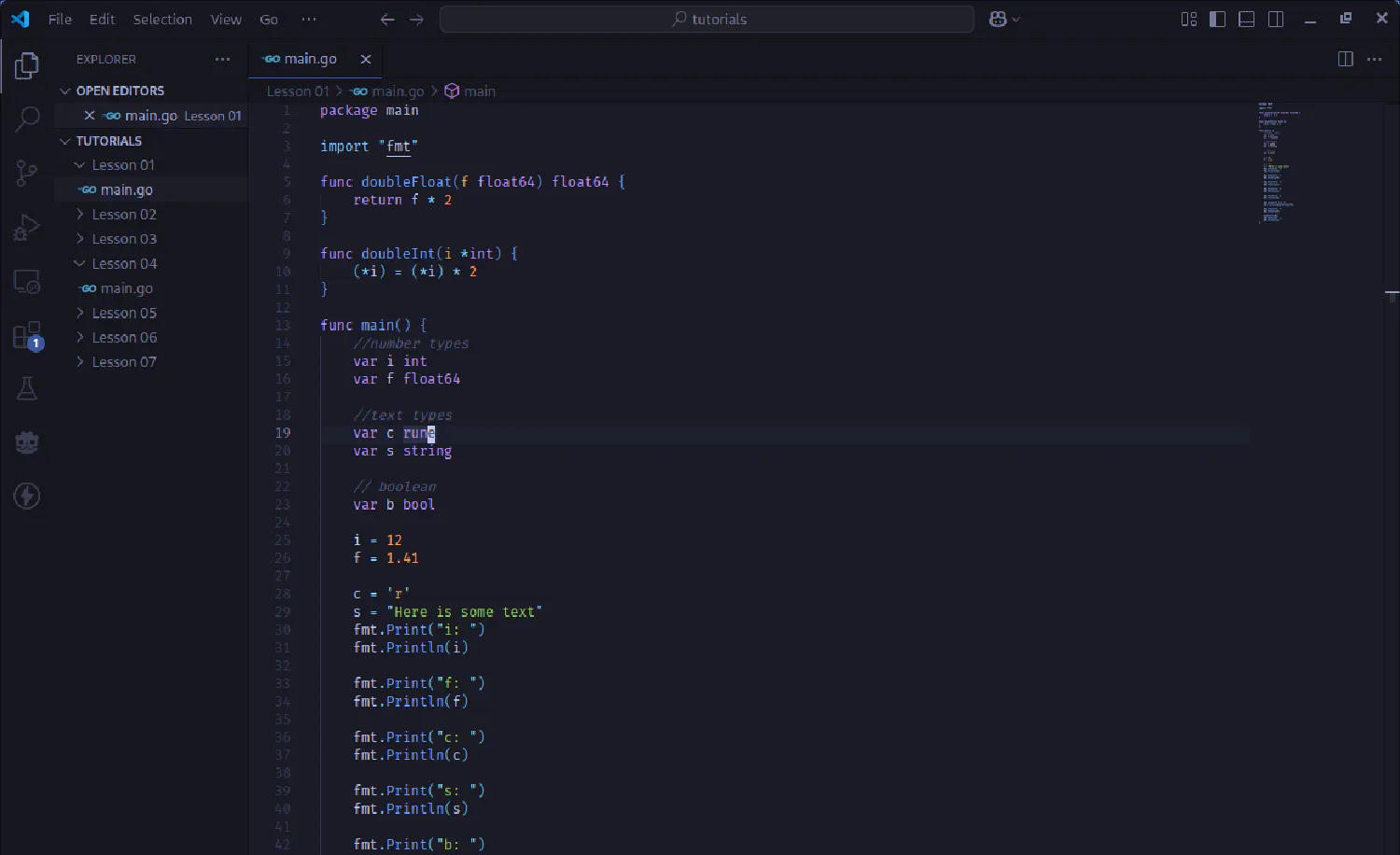

main.go:

package main

import "fmt"

func doubleFloat(f float64) float64 {

return f * 2

}

func doubleInt(n *int) {

(*n) = (*n) * 2

}

func multiply(a int, b int) int {

return a * b

}

func multiReturn(i int) (int, int) {

return i - 1, i + 1

}

func main() {

//number types

var i int

var f float64

//text types

var c rune

var s string

// boolean

var b bool

i = 12

f = 1.41

c = 'r'

s = "Here is some text"

fmt.Print("i: ")

fmt.Println(i)

fmt.Print("f: ")

fmt.Println(f)

fmt.Print("c: ")

fmt.Println(c)

fmt.Printf("c: %c\n",c)

fmt.Print("s: ")

fmt.Println(s)

fmt.Print("b: ")

fmt.Println(b)

fmt.Print("f * 2: ")

fmt.Println(doubleFloat(f))

fmt.Print("f: ")

fmt.Println(f)

doubleInt(&i)

fmt.Print("i: ")

fmt.Println(i)

fmt.Println(multiply(2, 3))

i1, i2 := multiReturn(i)

fmt.Printf("%d:%d", i1, i2)

}

Comments

I know this subject wasn’t included in the title of this post, but I would be remiss to exclude it. If you want (and you should want to) make notes in your code you can do so by including “comments”. Comments are ignored by Go, so you can add any notes you like. To make a single line comment start it with two slashes // anything on that line after the slashes will be ignored.

Variables

Variables are letters/words/symbols that represent a value of some sort. Remember in algebra formulas like: $$ a = b+c $$ a,b, and c are all “variables” that represent numbers. In programming, variables can represent a lot more that just numbers too. What thing a variable represents is referred to as a “type”. Lets take a look at some of the main types in Golang. My most languages will have similar. Here are a few of the main types in Golang.

Numbers

There are different types of numbers in Golang. Which one you should choose will depend on your use case. Note that depending on how big a number you need, you may have to additional include a large or smaller bit width to the variable. For instance if you have a large enough int you will need to set the type to int64, or if it is small and you want to conserve memory use int8. Same goes for float.

int, int8, int16, int32, int64

int stands for integer. If you don’t recall, integers are whole numbers (-1,1,2,145, etc)

float16, float32, float64

float stands for floating point. These are numbers with fractional parts. (3.14, 25.5, 1.75, etc)

rune

rune is how golang handles what most languages refer to as char, which is short for character. This represents single letters, symbols, etc.

string

string is a grouping of runes/characters. For example the word “pickle” would be a string. “Hello world!” would also be a string.

bool

bool stands for boolean. Booleans can have two values, true or false.

Declaring and Assigning

Declaring a variable means you are creating a variable with a specific name and type. Let’s look at lines 14-23:

//number types

var i int

var f float64

//text types

var c rune

var s string

// boolean

var b bool

Here we first see two numeric variables being declared. the keyword var specifies that what is to follow is a definition of a variable. In this case i is of type int and f is a float64. Declarations of rune,string,bool (c,s,b) found here as well.

At this point in the code, what are the values of these variables? In Go, each type has a default value. The numeric types will be 0. The text types will be "" aka empty. The boolean will be false. What if we want them to hold different values? Once they are declared we can assign values as seen in the next lines:

i = 12

f = 1.41

c = 'r'

s = "Here is some text"

The code above is pretty self explanatory. Note that there are two other ways of doing a declaration and assignment all at once. For instance, i could have been declared and assigned the value 1 by doing:

var i int = 1

Another way that is somewhat unique to Go is

int := 1

In this case adding the colon before the equal sign will tell Go to create a variable i and its type should be the type of whatever is on the right side of “:=” Go will make an educated guess that 1 is an int. When to use one method or another will depend on the use case. Functions Functions are reusable sections of code. If we go back to the algebra analogy, you may recall y=mx+b could also be written as:

$$ f(x)=mx+b $$

f is a function that when you give it x, it will multiply it by m and add b to it. Similarly, you can pass variables to functions in Go, have it perform an operation with them and give back a result. While this is not in the code example, here is what f(x)= mx+b might look like in Go:

func f(x int) int {

m := 2

b := 1

return x*m+b

}

Lets break this down. We start with the key func so Go knows what is to follow is a function. We then give it a name f. Inside the parentheses, we tell it the variables that can/should be given to it (integer x). After that we let it know what result should be given when the function is called, another integer. Then we use curly braces {} indicate the start and end of the actions to be performed. We declare and assign variables m and b. Then we tell it to return, or give the result of mx+b. * is the symbol for multiplication. A list of the other arithmetic operators can be found here. Leave comment if you would like an article diving into more depth on them.

Now let’s take a look at a function in the example code:

func doubleFloat(f float64) float64 {

return f * 2

}

doubleFloat take a variable f of type float and returns 2*f. Pretty simple, right? If f is 1.41, doubleFloat will return 2.82.

You can also create functions that require more than one argument. Just separate them with a comma:

func multiply(a int, b int) int {

return a * b

}

The next concept is fairly unique Golang. A function can return multiple results:

func multiReturn(i int) (int, int) {

return i - 1, i + 1

}

Here we see the function take an integer and returns two values. Calling this function would look like:

i1, i2 := multiReturn(i)

Lets say for some reason you only planned on using one of the values. If you assign it to a variable and don’t use it, Golang produces an error. So:

i1, _ := multiReturn(i)

You can use an underscore _ to basically ignore one of the return values. Multiple return values comes in handy when dealing with error handling in Golang. We will cover this in a future article.

main

Programs needs to know where to start. In the case of Golang and many others, there is a special function called “main”. This is the first function to be executed. Note that any global definitions would be available at this time as well.

Imports and Packages

Often you will want to reuse code in multiple programs, or utilize code somebody else has written. This is where packages and importing step in. Think of packages as groups of reusable code that you can import into your application. Check out the first few lines of our program:

package main

import "fmt"

The first line is stating what our own package is called. main is used so go know which package houses the entry point of our program. We will look at how to create other types of packages in future articles. The next line is importing a package called fmt. This package comes default with Golang. It comes with functions that allow formatting and printing data. Let’s look some of the ways we use it in our program:

fmt.Print("i: ")

fmt.Println(i)

fmt.Print("f: ")

fmt.Println(f)

fmt.Print("c: ")

fmt.Println(c)

fmt.Printf("c: %c\n",c)

First we see fmt.Print. This is saying use the Print function from the fmt package. It will print what ever string you want to STDOUT (in this case the terminal). The next line calls fmt.Println. This does the same thing as Print, but also moves the cursor to the next line. (It’s kinda like hitting the enter key.) What about the last line? Printf stands for “Print Formatted” It exists in many languages and works pretty much the same way. You pass as special string that can contain variables of it own, denoted by “%” You can checkout the Golang docs here. In this case we are telling it to print “c: " followed by %c which will be a rune/character then “\n” which is short for a new line. Since a variable was specified int the first argument to the function we have to pass and additional argument, which needs to be a rune, in this case “c”.

Scope

For now you can think of scope as where do we have access to a variable. In general, a variable’s scope is confined to inside the curly braces of where it was defined. If it was declares outside curly braces, then it is considered a global variable, and can be accessed almost anywhere. For reasons saved for another topic, we should minimize the usage of global variables. Let’s look at an example from our program. We see that f was declared and set to 1.41, and then was passed to doubleFloat. Why do we need to pass f, if f is used in doubleFloat? The answer is scope. The f in main function and the f in doubleFloat are in different scopes and therefore not the same f.

Pointers

While “normal” variables store a value, pointers store a location of where to find the value. Pointers are denoted by putting an * in front of the type. This time it doesn’t mean multiply. In the previous example i points to an int value.

func doubleInt(n *int) {

(*n) = (*n) * 2

}

What do you think it does? Well, it takes a variable i which is of type *int and seems to return nothing. What is going on here? n is a pointer to a location in memory that stores an int. That means the function will have access to modify the value in that memory location. So, if n points to the value 12, after this function is called the value there will now be 2 times greater. Now you may wonder what (*n) means in this function. This is referred to as de-referencing. So we are saying we want the value stored at the location n is pointing to rather than the pointer itself. Since n has not changed where it is pointing to, it will now reference the value 24. When functions take arguments that are pointer they are referred to “pass by reference”, while the others are “pass by value” Which method you choose will depend on the application.

Conclusion

Our first program contained the basics you need to get started programming in Golang. Look at the code again, and see if you still have questions about how it works. Play around with the code a bit. If you have any questions, leave a comment. In our next lesson we will learn about other more complicated data types called structs.