Beginning Programming Lesson 08

Now that we have the basics down, let apply them to something more real, and perhaps the previous concepts covered will become more clear. When I learn a new programming language I generally start with trying to create a program to solve the Tricky Triangle. If you have ever been to Cracker Barrel, you know what it is. It goes by some other names too, but it is usually a triangular piece of wood with holes in it with enough golf tees to fill all but one whole. You play a checkers like jump rules where you remove the peg you jumped over You keep going until you have no available moves left. The goal is to only have one peg left. The code for the lesson is here.

Building the Game

Before we try to “solve” the game we first need to build the game in code.

The Board

Let’s create a struct to represent the board:

type Board struct{

}

Notice that the board has 15 holes in it. Each hole can either have a peg in it or be empty. So lets create a struct to represent a hole and keep track of whether it is empty or not:

type Hole struct {

empty bool

}

Let’s number the holes in the board from 0-14 starting from the top and going left to right. Then we can keep track on each in an array stored in the Board struct

type Board struct {

Holes [15]Hole

}

Awesome! Let’s create a way to add/remove a peg to/from a hole. While we are at it, let’s add a method it get whether the hole is empty or not:

func (h *Hole) AddPeg() {

h.empty = false

}

func (h *Hole) RemovePeg() {

h.empty = true

}

func (h Hole) Empty() bool {

return h.empty

}

It would be nice to be able to see the board. Let’s add a way to represent the status of a whole, and then the status of the board to the terminal:

func (h Hole) String() string {

if h.empty {

return "○"

}

return "●"

}

func (b Board) String() string {

ret := ""

ret += fmt.Sprintf(" %s\n", b.Holes[0])

ret += fmt.Sprintf(" %s %s\n", b.Holes[1], b.Holes[2])

ret += fmt.Sprintf(" %s %s %s\n", b.Holes[3], b.Holes[4], b.Holes[5])

ret += fmt.Sprintf(" %s %s %s %s\n", b.Holes[6], b.Holes[7], b.Holes[8], b.Holes[9])

ret += fmt.Sprintf(" %s %s %s %s %s\n", b.Holes[10], b.Holes[11], b.Holes[12], b.Holes[13], b.Holes[14])

return ret

}

Time to test it out:

func main(){

var board Board

fmt.Println(board)

board.Holes[4].AddPeg()

fmt.Println(board)

board.Holes[4].RemovePeg()

fmt.Println(board)

}

The example above should first show the board empty then show a peg in the center of the board, and finally show it empty again.

We have the board created, but we don’t have the game coded yet. We need a way to make sure valid moves are made and when the game is over, and if we won.

The Game

We are going to want to keep track of the current status of the game. A game consists of the Board and the moves that took place:

type Move struct {

To int

From int

}

type Game struct {

board Board

moves []Move

}

Let’s also provide a way to initialize the board, allowing the player to select which hole should start empty:

func (g *Game) Start(openSpot int) {

for i := 0; i < len(g.board.Holes); i++ {

if i == openSpot {

g.board.Holes[i].RemovePeg()

} else {

g.board.Holes[i].AddPeg()

}

}

}

Technically the default value of a boolean is false, so we wouldn’t need to call RemovePeg(), but I did for the sake of clarity. It would also be nice to display the board, and access the current “score”:

func (g Game) DisplayBoard() {

fmt.Println(g.board)

}

func (g Game) Score() int {

return g.board.Remaining()

}

All the Right Moves

The board isn’t exported, so we need to provide a way to allow the player to make a move, but we don’t want them to be able to cheat either. So, we need a way to determine if a move is valid. For one, a player can’t move a peg anywhere on the board e.g, a player can’t move a peg from position 0 to 10. Given there is a peg in between to jump over, what are all the valid moves?

var potential_moves [15][]int = [15][]int{

{3, 5},

{6, 8},

{7, 9},

{5, 10, 12, 0},

{11, 13},

{0, 3, 12, 14},

{1, 8},

{2, 9},

{6, 1},

{2, 7},

{3, 12},

{13, 4},

{10, 3, 14, 5},

{11, 4},

{12, 5},

}

Here I created an 2D array to keep track of the valid moves. To find the valid moves for the peg in hole 0, we look at the values stored in the 0th position in the array (3 and 5).

There are still three more things to consider when evaluating if a move is valid. First, is there a peg in the position the player wants to move from? Second, is the hole the player wants to move the peg to empty? Third, is there a peg in between to jump over? Knowing this, let’s create a method to check for a valid move:

func (g Game) isValidMove(from int, to int) bool {

if g.board.Holes[from].Empty() || !g.board.Holes[to].Empty() {

return false

}

for _, s := range potential_moves[to] {

center := (from + to) / 2

if s == from && !g.board.Holes[center].Empty() {

return true

}

}

return false

}

The tricky part here was how to determine the hole between the peg the player wants to move and the hole they want to move it to. Turns out the average of the to and from positions produces the position of the hole in between. Remember that the positions are stored as int. So, the resulting average will also be int e.g., (1+8)/2 = 4, not 4.5.

Now that we know what the valid moves are, we can detect when game is over i.e. when there are no valid moves left:

func (g Game) GameOver() bool {

for i, h := range g.board.Holes {

if h.Empty() {

for _, s := range potential_moves[i] {

if !g.board.Holes[(s+i)/2].Empty() && !g.board.Holes[s].Empty() {

return false

}

}

}

}

return true

}

We can also create a method to allow the player to make a move, and store that move for future reference:

func (g *Game) Move(from int, to int) error {

if g.isValidMove(from, to) {

center := (from + to) / 2

g.board.Holes[from].RemovePeg()

g.board.Holes[center].RemovePeg()

g.board.Holes[to].AddPeg()

g.moves = append(g.moves, Move{From: from, To: to})

return nil

}

return errors.New("not a valid move")

}

Our tricky triangle package now has everything we need to play the game. If we really wanted to “manually” play the game, we could add some improvements to the UI components, e.g., number the holes so when the user doesn’t have to count to determine which move to enter. However, we want the program itself to solve it, so it is less of an issue.

package main

import (

"github.com/jlhags/tutorials/lesson_08/trickytriangle"

)

func main() {

game := trickytriangle.Game{}

game.Start(14)

solveGame(&game)

game.DisplayBoard()

}

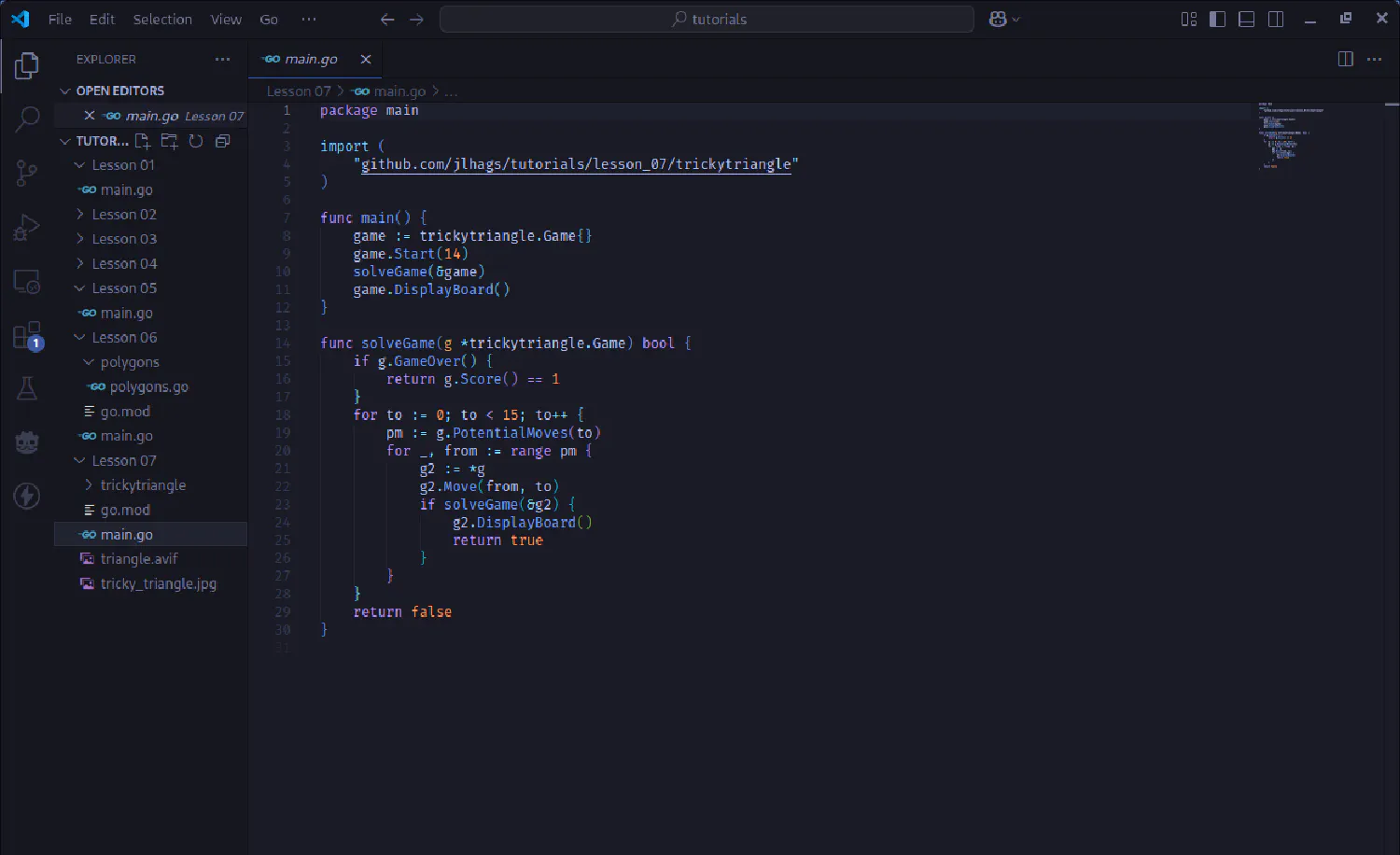

Here we create a Game and set the empty spot. Then we call a function called solveGame, and like magic, it solves the game. It’s not really magic, since well… we have to implement that function. This isn’t a game theory tutorial, I won’t go into great detail. We are going to use something called Minimax. The basic idea is, we spin off a new instance of the game for ever possible first move, and for each one of those games, we make every possible second move, and continue doing the same until one of the games results in a win. This also sounds a lot like recursion. So, we will use it in the solution. Our stop condition will be when the game is over. To decide which iteration of the game is the “best” we will just take the first one we detect that only has one peg left:

func solveGame(g *trickytriangle.Game) bool {

if g.GameOver() {

return g.Score() == 1

}

for to := 0; to < 15; to++ {

pm := g.PotentialMoves(to)

for _, from := range pm {

g2 := *g

g2.Move(from, to)

if solveGame(&g2) {

g2.DisplayBoard()

return true

}

}

}

return false

}

If we were to run the program now, you might notice something odd. It prints out the moves in reverse order. It is just the nature of the recursion. Not a big deal. We could try fix it, but it gives us a a good enough visual representation of the game that was played, so we can check to make sure it worked correctly. Also we should check a few other starting positions as well. Once we feel confident that it works. We can change the output to be the list of moves taken in the correct order:

func solveGame(g *trickytriangle.Game) bool {

if g.GameOver() {

if g.Score()==1 {

g.PrintMoves()

return true

}

return false

}

for to := 0; to < 15; to++ {

pm := g.PotentialMoves(to)

for _, from := range pm {

g2 := *g

g2.Move(from, to)

if solveGame(&g2) {

return true

}

}

}

return false

}

Conclusion

We put together all the concepts we learned into a semi-useful program! Is there anything you would do to improve it? Is there a different way to store the valid moves that wouldn’t require the loop is isValidMove? How might you change the trickytriangle package if you wanted a human to play the game?